Urban Greening - University of Cambridge - Flood Mitigation + Food Provision

How urban growing can revolutionise vacant spaces across East Anglia's towns and cities

Dr Rebecca Ward is from the University of Cambridge's Energy Efficient Cities Initiative. Here she argues how urban planting can help to mitigate the effects of extreme weather caused by climate change, and provide food for an increasingly urbanised population.

Plants in cities contribute to urban greening in many ways, from providing shade and humidity and absorbing surface water to providing barriers to road noise and pollution. As our climate changes, we may be increasingly exposed to more extreme weather events such as heatwaves and droughts, but also severe storms and floods. By increasing the amount of urban planting and making nature part of the city environment, the worst impacts of the weather can be counteracted.

While hard surfaces can only absorb or reflect heat, planted surfaces can cool the air above them and trees provide shade. Equally, flood water has nowhere to go on a hard surface but into the drains which can swiftly become overwhelmed. By comparison, a planted surface allows the water to soak away more slowly and can help to prevent flash flooding. Inside buildings, plants have a cooling and humidifying impact on their surroundings and have been shown to be able to absorb some airborne pollutants.

The Energy Efficient Cities initiative (EECi) at the University of Cambridge Department of Engineering has at its heart the ambition to understand how we can reduce our energy demand and environmental impact in towns and cities. One aspect of our mission is looking at the importance of plants in the urban setting, both inside and outside buildings.

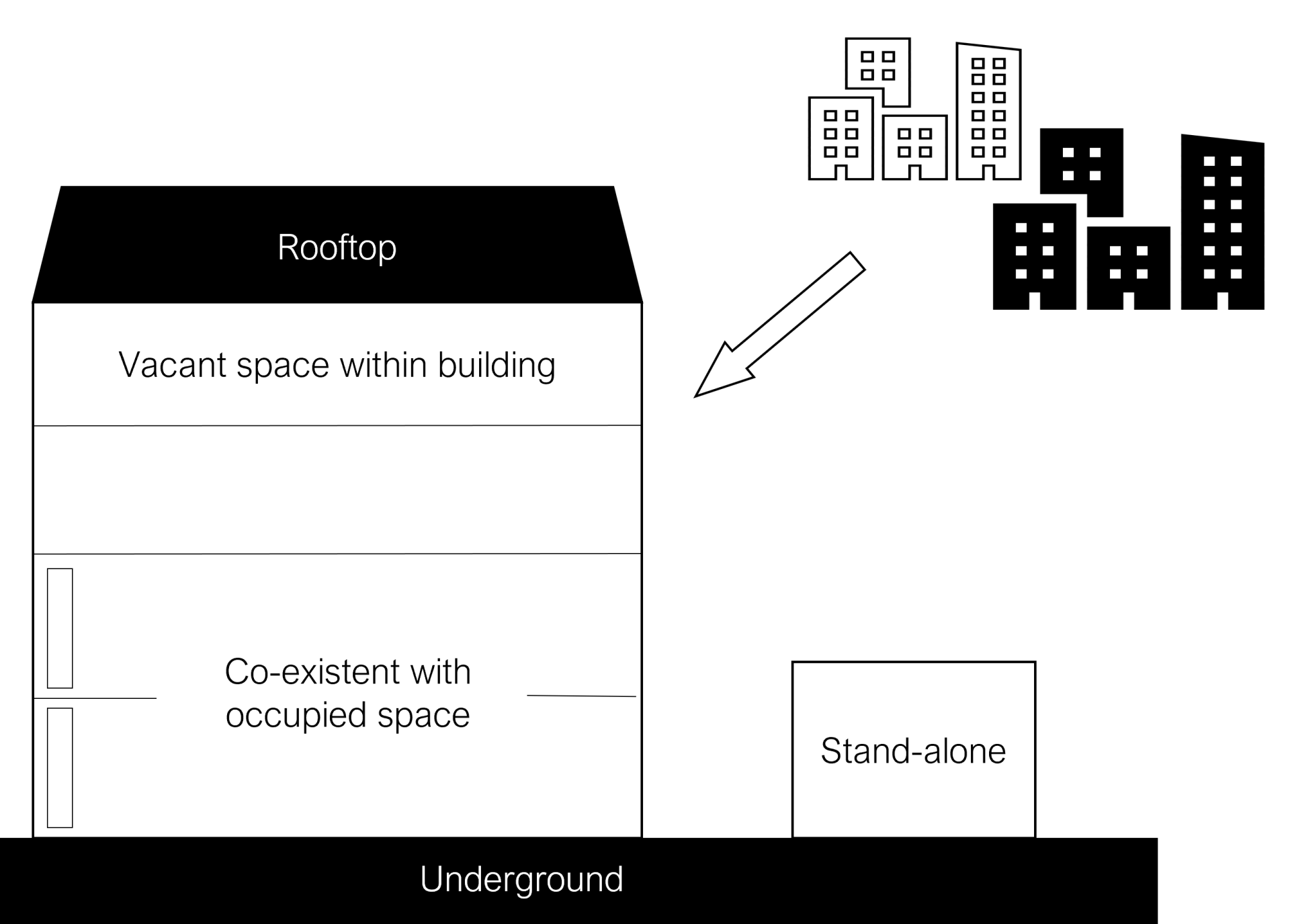

At the EECi, we are interested in how we can use our understanding of how buildings are operated in cities to learn about how to make the best use of planting designs. We are particularly interested in urban farming and the way in which derelict spaces might be used to produce food and at the same time benefit the environment.

Increasing urban populations mean that larger quantities of food have to be brought into the city on a daily basis. This inevitably leads to more food miles and a higher carbon footprint. Producing fresh food in the heart of the city can help to address this challenge and brings other benefits in terms of job creation, reduction of pollution and less food waste. Encouraging plant growth and food production in our schools can help children to better understand where their food comes from. Including communal growing spaces such as allotments or gardens in urban re-generation projects can have positive physical and mental health benefits too.

EECi, in collaboration with the Centre for Smart Infrastructure and Construction, have been working to help improve the efficiency, productivity and profitability of urban farming in collaboration with the world’s first underground farm, Growing Underground.

Located 33 metres below Clapham High Street in London, this farm has been developed in former World War II air raid shelters. While the intention was to join the shelters into the London Underground system in the post-war period, this never happened and the tunnels sat unused for decades. In 2015, co-founders Richard Ballard and Steve Dring started to develop the site for food production. Now the fully productive farm grows micro salads, such as pea-shoots, basil, coriander, pink radish and salad rocket, which are delivered to New Covent Garden Market less than a mile away for distribution to restaurants and supermarkets across London.

The plants grow without soil (‘hydroponically’) on recycled wool carpet mats, using 70% less water than conventional agriculture methods. The primary cost is the energy cost of the LED lights, but as these provide both lighting and heat no additional heating is required and plants can be grown year-round. The farm grows 12 times more per unit area than a traditional greenhouse, but the energy costs are just four times more per unit area.

Our role at Cambridge has been to help the farm owners to understand how to make the best use of the space available in terms of producing the most crop for the lowest cost and least waste of resources.

To do this, monitors have been installed which record all aspects of the tunnel and growing environment, from temperature and relative humidity to the energy demand of the lighting and ventilation system. Using these data in conjunction with crop harvest data has made it possible to gain insights into the farm workings, including for example identifying areas of the farm where different crops grow better.

Methods have also been developed for forecasting farm conditions and the impacts of changes to the operation strategy. This could be, for example, an increase in ventilation rate or a change to the number of hours the lights are switched on. The monitoring data and models are being combined into a visualisation platform, or ‘digital twin’, in conjunction with software engineers from The Alan Turing institute in London. The benefits of this are that the farm managers will be able to see immediately how the farm is performing, and the digital twin will be able to monitor, learn, feed back, and forecast information that can make the real-life twin perform better.

• The Energy Efficient Cities initiative is headed by Dr Ruchi Choudhary. For more information on our involvement with Growing Underground see here.

• Read more about the Centre for Smart Infrastructure and Construction

• Written by Dr. Rebecca Ward, Research Associate, Data-Centric Engineering, The Alan Turing Institute. rward@turing.ac.uk

WildEast Blog

Powered by LocaliQ

Follow Us

SIGN UP FOR NEWS & UPDATES

Newsletter Sign Up

Thank you for signing up to our newsletter.

Please try again later.

Privacy / Terms & Conditions / Sitemap